The decor of the University of Buenos Aires’ (UBA) College of Social Sciences was never known for being minimalist, but this week, the halls are an explosive menagerie of campaign banners, proposals, and slogans. The thirteen colleges of Argentina’s largest public university are in the last day of elections for key student decision-making bodies: Student Center, Board of Directors of each college, and Board of Directors for each major. After seven months of austerity and attacks on education by president Javier Milei, the outcome of these elections will determine the political and strategic orientation of the Colleges’ responses to Milei for the next two years.

Milei’s shock therapy has raised the stakes of University elections by putting students, professors, and other university workers in dire economic straits. This week, the University of San Martín released a study which found that 85% of public university professors are paid wages are below the poverty line. This has created a situation of “pluriemployment” in which university professors must work second and third jobs to make it to the end of the month.

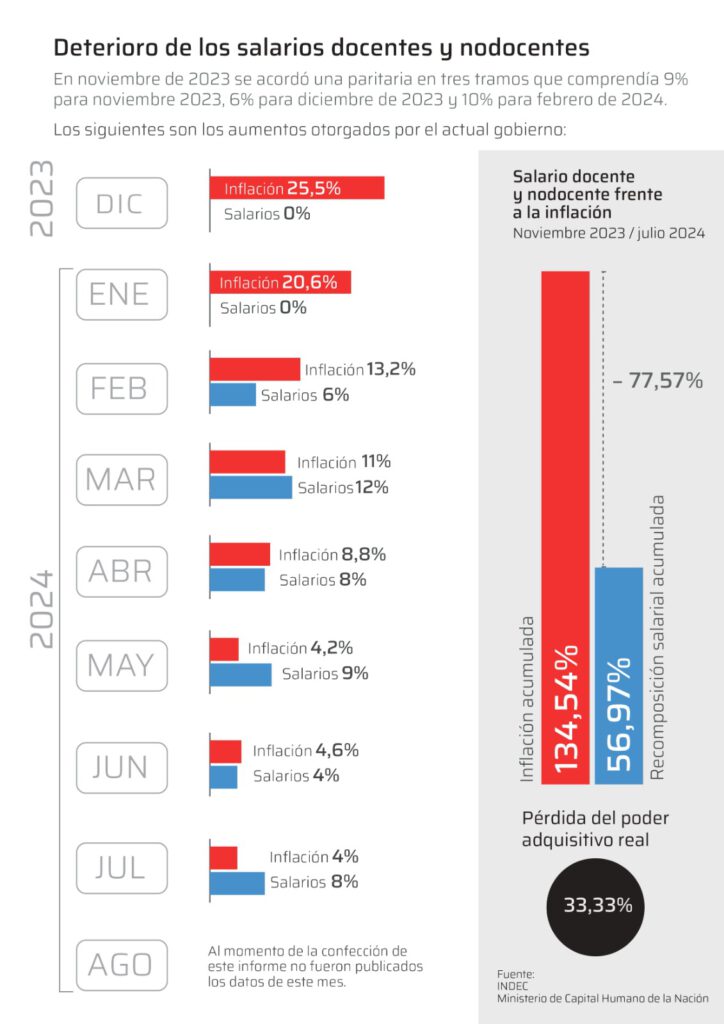

The graphic below shows monthly inflation in Argentina compared to professors’ wages, with the latter totaling nearly 80% below inflation over 8 months. Taking into account the price of a basic monthly basket of goods, the study calculates that professors have seen roughly a ⅓ loss in their wages’ purchasing power since December.

The massive Nationwide March for Education in April may have saved Argentina’s public universities from a shutdown, but the future of education under Milei remains uncertain. Following the march, the government conceded minor monthly budget increases, leading UBA’s Upper Council to lift the budget emergency it had delcared earlier that month. However, some feel that the Council’s decision was premature, since university workers remain in precarious conditions. The controversy of lifting the budget emergency looms large over the current elections, especially for students who feel that the Student Center and Board of Directors are not combative enough in defending students’ and professors’ needs. In the College of Social Sciences, the United Left and Workers’ Front (FIT-U, for its initials in Spanish) has used the decision as evidence that the current Center, headed by a supposedly center-left coalition that is pacted with right-wing groups, is not deeply invested in professors’ struggle for a fair wage.

In the College of Social Sciences, the electoral dispute is largely playing out along national party lines. This is due in large part to the fact that most student political organizations are directly linked to one of the country’s main national parties. Presidential candidates for the Student Center adopt their national party’s talking points and count on its electoral base in the College to carry out their campaigns. This leads to a situation in which the alliances and infighting between student groups not only mirror Argentina’s national political landscape, but amplify existing antagonisms between progressive and reformist sectors.

As much in national as university politics, Argentina’s socialist left has accused the center-left Peronist sectors of being complicit in Milei’s extremist reforms. At the end of last year, Peronist representatives, elected by the Board of Directors, voted to stop providing healthcare plans for retired professors. One national Peronist delegate who is popular among youth also recently supported making teachers essential workers, which would make it illegal for them to go on strike. This is directly opposed to the FIT-U’s vision for the Student Center, which they say must support professors’ strikes and push further in negotiations with the ruling party.

Perhaps most concerning, the current Student Center representatives have not organized any collective action between students and professors. On the contrary, they kept the College open on strike days early this semester, undermining professors’ efforts to collectively withhold their labor. Earlier in the year, joint student-professor demonstrations were central for pressuring the government to increase the university budget. However, many of these demonstrations were organized by independent groups, not the Student Center itself. Because of this perceived inaction on the part of the Student Center, this week’s elections are an opportunity for leftist groups who are looking to channel more active militant politics into official university spaces.

In the Facultad of Social Sciences, student elections are reflecting disputes in the national landscape, especially the willingness of the country’s ostensible center-left to pact with the right-wing government. For instance, Milei’s party, holding just seven of seventy-two seats in the Senate, received key votes from provincial Peronist governors to pass a new Foreign Investment Regime that entices foreign capital with tax cuts, privatizations, and no environmental controls. While Peronism has always housed important sectors of the right, these votes in favor of a bill which baldly debilitates workers’ rights and Argentina’s national industry raises questions about the priorities of the supposedly pro-worker, pro-industry party. The FIT-U argues that a parallel hipocrisy is being magnified in the university elections, in which the Student Center has painted itself as the defenders of the College of Social Sciences, despite joining late and tapping out early in the fight for dignified wages, as well as electing representatives who openly oppose teachers’ right to strike.

In this sense, this week is not a symbolic scramble for whose banner will fly against Milei’s austerity, but whether the Student Center will mobilize against austerity at all. The biggest question at stake is: what is the political role of students in guaranteeing their own education? As many have pointed out, the poverty of professors has direct bearing on the quality of students’ own learning. What responsibility do students have to act in solidarity with professors, and is mobilizing against Milei’s economic reforms necessary to protect the university? By tomorrow, we’ll know how the students decide.