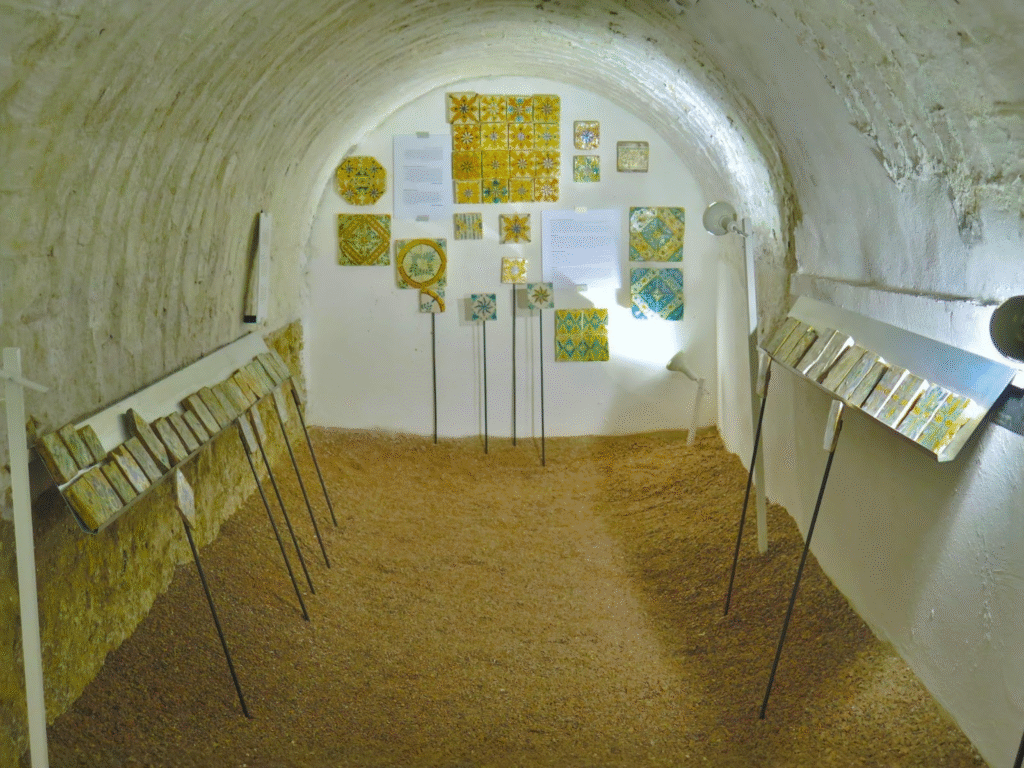

Descending the steps beneath Dar Ben Gacem feels like entering a secret vault. The ceilings are low and the air is cool, a reminder that just a few decades ago, this space served as an enormous refrigerator for the multi-family house.

Today, however, the former refrigerator is home to one of the most extensive tile galleries in Tunis. It is the private collection of Mohamed Massaoudi, but as part of Dar Ben Gacem’s heritage and restoration project, it is open to the public for free.

Six unassuming monochrome tiles, each no bigger than a Post-it note, inaugurate the space. Yet the plaque beside them reveals their true significance: crafted in the 13th century, they are among the nation’s oldest surviving tiles.

Continuing down the corridor, I follow Tunisian tiles through time, watching their motifs morph, fade, and reappear across the centuries.

Sihem Lamine, a historian of Islamic architecture, explains that the collection is one-of-a-kind in the country, making it a magnet for researchers and tourists alike.

“You see all the pieces and techniques right next to each other, so you can compare and analyze them,” Sihem says. “There’s nowhere else you can see all these styles together, at the same time.”

All the tiles featured in the museum were produced in Tunisia, so visitors get a sense of the country’s distinctive artistic flavor.

“The human hand is something that speaks volumes about where things come from, about techniques—it’s how a place’s visual identity is built,” she explains.

Tiles were at the epicenter of Tunisian ceramic production for many centuries, making them a window into the changing empires, technologies, and artistic expressions of Mediterranean society. One of the most transformative of these shifts was in the 16th century, when the Ottoman conquest revolutionized tile production with a distinctive visual tradition called Iznik. Iznik ceramics prominently featured distinctive blue dyes and motifs of curving, serrated flowers, which can be clearly seen in Tunisian tiles from that period. When it was made, a single one of these prized tiles cost as much as a sheep!

Another key social change in the history of Tunisian tiles was the expulsion of Moriscos from Spain in the 17th century. Moriscos were often skilled artisans, and upon resettling in the Maghreb in the early 17th century, they mixed innovations from Renaissance Spain with local Ottoman and Hafsid influences. This demographic shift may have helped impulse one of the most recognizable and institutionalized ceramic traditions in Tunisia: Qallalin tiles. A combination of Ottoman calligraphy, floral motifs, and color palettes with the Spanish Majolica technique of tin glazing, Qallalin tiles flourished until imported industrial ceramics eclipsed them in the 19th century.

Even the limitations of production techniques influenced ceramic styles in surprising ways. For example, the 14th-century cuerda seca method of dying tiles left thin dark lines in between the colors. Even though these lines were an inadvertent byproduct of the dyeing technique, they became a distinctive aesthetic that endured for centuries. Even as more advanced dyeing techniques emerged in the 17th century, artisans deliberately echoed the lines, creating what became known as faux cuerda seca.

Interestingly, tiles are themselves a technological innovation: they act as a building’s “second skin,” preventing humidity from eroding a building’s plaster rendering. This is especially important in seaside cities like Tunis, where year-round humidity can quickly destroy unprotected walls.

Until the advent of industrial technology, however, the practical advantages of tiles remained inaccessible to everyday people. Instead, tiles were primarily produced for upper-class residences or religious buildings, as their manufacture required firing in wood-fueled ovens—a costly and energy-intensive process.

While tiles certainly underwent a renaissance during the 17th and 18th centuries—as evidenced by the Qallalin tradition—it wasn’t until industrialization during the 19th century that tiles began to cover Tunis in the way we recognize now. New techniques, which made heating and coloring tiles far less labor-intensive, allowed for extensive decoration: “Everywhere Tunisians could put tiles, they put tiles,” Sihem says.

In fact, some of the post-18th-century tiles in the Dar Ben Gacem museum can also be found in ordinary homes in the medina. Part of the reason is that, when a house is going to be demolished, the tiles are often saved and reused on the new structure. This cycle of preservation gives the tiles a new life, folding historic influences into a modern structure.

In this sense, tiles are not simply decorations, but a living history. They are a testament to the diversity of people who have lived in Tunisia—their tastes, cultures, and handiwork. The Dar Ben Gacem gallery not only preserves but breathes life into these tiles and their stories.

“Now that the museum is here, it may seem so obvious: of course, this is what should have been done,” Sihem says. “But it actually takes a lot of courage.”

In the absence of a centralized agency for protecting Tunisian ceramics, the responsibility of saving, studying, and understanding Tunisia’s rich ceramic history falls to private citizens. By making the tiles publicly available, Dar Ben Gacem sets a precedent for citizens and collectors to protect and enjoy Tunisia’s visual heritage.

“The alternative is people who write PhD dissertations, and their ceramic catalogs remain in a book,” Sihem explains. “But when you see a tile, when you’re close to it, that’s when you really begin to understand the tile.”

For Sihem and others, tiles aren’t just valuable as objects of research, but as markers of Tunisia’s history and identity.

“The colors, influences, and iconographies are an incredible blend—you can’t mistake Tunisian tiles when you see them anywhere in the world,” Sihem says. “Pottery and ceramics tell who you are.”