This year, Christmas in Venezuela came early—very early. Following his dubious presidential victory in July, Nicolás Maduro smelled the holiday spirit in the air. And so it was: on Tuesday, October 1, thousands of Venezuelan children woke up to find Santa had come down the chimney. Maduro has moved Christmas forward (“as a thank you to the pueblo”) every year since 2015.

As Venezuelans sat down for Christmas dinner, in Argentina, hundreds of students occupied their universities overnight in anticipation of a second Federal University March. The march was organized in response to president Javier Milei’s promise to veto a bill which would tie public university funding to inflation, adjusting professors’ salaries every two months. The bill was approved by both chambers of Congress, but did not receive a veto-proof ⅔ majority. On Wednesday, after over a million people took to the streets nationwide to demand financing for public universities, Milei officially vetoed the bill.

Between the first and second Federal March for University, Argentina’s social and economic landscape has taken on new dimensions: in the last 6 months, 3 million more Argentinians have fallen into poverty; today, over half of the country’s population cannot afford a monthly basket of basic goods. Argentine industry has also taken a hit: “between December 10, 2023, and July 4, more than 38,000 crisis prevention procedures were filed, 40% more than in recent years,” the Buenos Aires Herald reported in July. These procedures, which companies file in anticipation of large layoffs, reflect a fall in industrial activity and the inability of small- and medium-size companies to compete with foreign products. These indicators undermine Milei’s narrative that slashing social services and giving tax cuts to multinationals are sacrifices that benefit the economy. Rather, small- and medium-sized national businesses have been the first casualties of Milei’s thirst for foreign capital.

“Behind us are our workers and the 10,000 companies that closed in the first semester, leaving 130,000 private sector workers in the street,” the President of National Entrepreneurs for Argentine Development said at a convention this week. “We need businesspeople to define national production, not economists.”

One way countries can lower inflation is by lowering consumer spending. Argentine economist Claudio Katz has asserted that the president has taken this measure to the extreme, successfully halting chronic inflation by simply bulldozing the country’s internal market.

The steady impoverishment of working-class Argentinians, whose wages have lost 30% of their purchasing power this year, has drastic implications for the country’s ability to achieve baseline learning outcomes—and not just in universities. Buenos Aires’ bachilleratos populares, autonomous high schools organized in response to the absence of public education in financially neglected neighborhoods, are reporting a precipitous drop in enrollment. Teachers at these schools told me that these days their students, 85% of whom are adults, are needing to work more hours to make ends meet. Without a high school degree, most bachillerato students already work low-paid, unsteady jobs. Adding that they must work overtime to cover their loss in real wages, many students are dropping out simply to put food on the table.

There has also been controversy over enrollment numbers at public universities. The Minister of Education, Carlos Torrendell, recently received criticism for suggesting that university officials have been “inventing students” on paper over the years to get more money from the government. The debate stems from a large disparity in the number of students who are officially enrolled in public university and the number of active students, which is much lower. Since university in Argentina is free and open to anyone, many students sign up but either never actually take classes, take breaks from university, or simply stop going without officially unenrolling. Torrendell’s comments struck a nerve for students who feel that this disparity between enrolled and active students is evidence of desertion, a problem which requires addressing the connections between living conditions and the accessibility of higher education. For these students, Torrendell’s assertion that University officials simply invented 600,000 students for financial gain is a distraction from the core issue: the cost of living crisis precipitated by Milei’s market deregulations is making it more difficult for students to finish school. Whether it’s accusing professors of brainwashing students, declaring “all majors except hard sciences are useless,” or, now, claiming that student desertion is invented by university bureaucrats, the administration’s political tack from Day 1 has been to debate the minutiae of “what really goes on in universities” rather than address the how its economic reforms affect the accessibility of education.

These discussions about enrollment in bachilleratos and universities demonstrate that bettering a country’s learning outcomes goes beyond education spending. The fight for education is deeply intertwined with struggles for dignified wages, affordable housing, and transportation, the minimum preconditions of being able to attend school at any level.

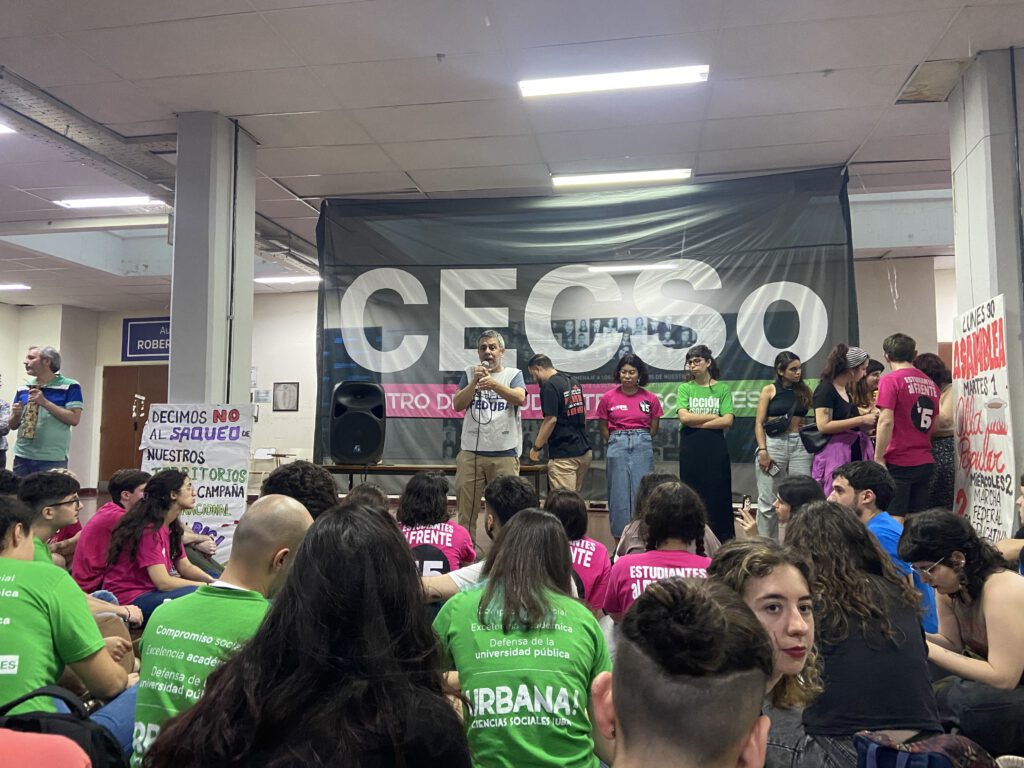

This intersectional nature of university students’ struggle was a central theme at the assembly held on Monday by the newly-elected Student Center of the College of Social Sciences (CECSo, for its initials in Spanish). Agus Romero, a militant of the United Leftist Workers’ Front, expressed concern that the new CECSo “still hasn’t come out in favor of the retirees, who are getting beat up every Wednesday,” in reference to the repression of weekly protests by retirees against the slashing of pensions. “The Student Center should be the first to say, ‘Our flag will be there every Wednesday in congress accompanying our elderly.’ The Student Center must come out against the privatization of Aerolineas Argentinas, they must be at the manifestations with the medical workers at Hospital Garrahan—that’s constructing resistance, that’s constructing popular power, that’s where we have to aim.”

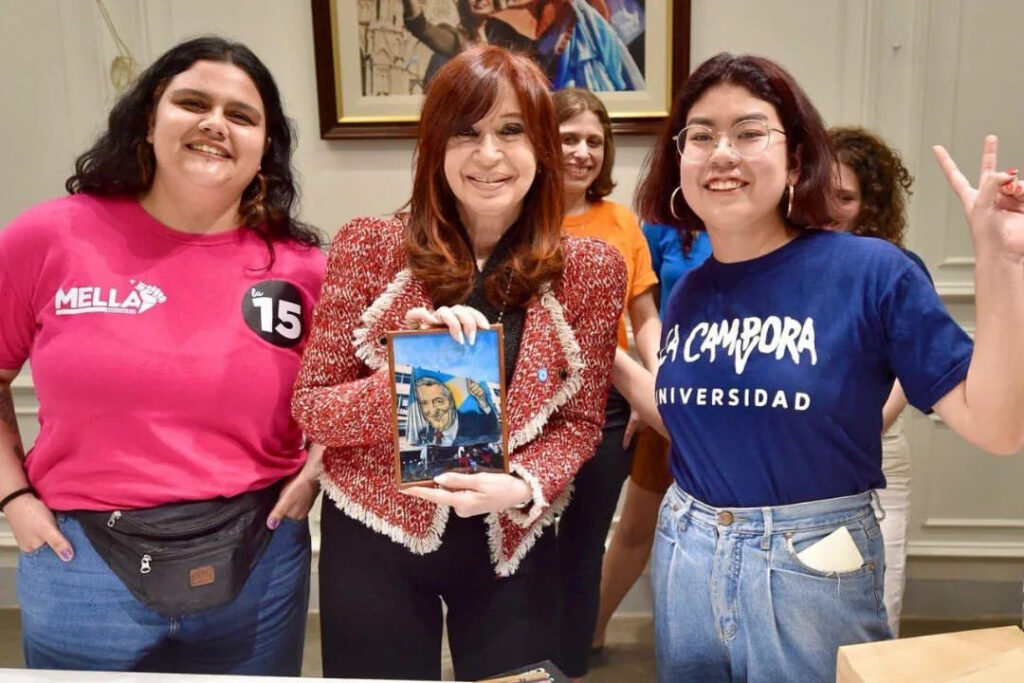

In last month’s student elections, a left-of-center group called La 15 eked out a victory for the CECSo over the incumbent center-right coalition La UES. In a wonderfully confusing turn typical of Argentine politics, both the former and newly elected CECSo groups belong to a political current called Peronism. Peronism is a political ideology which is very particular to Argentina and has historically housed both left- and right-wing political groups concurrently. There are endless books written about Peronism, and many Peronists themselves joke about its dizzying contradictions. Nevertheless, it remains one of the most forceful political movements among working-class Argentinians.

As I explained in my last blog, political student groups in the University of Buenos Aires typically have direct ties to national parties, similar to if the President of UCSB’s Associated Students used the Democratic Party symbolism, political program, and voter network in their campaign. In general, national political parties in Argentina have student associations as early as high school, where students can become involved in the party. At the university level, student politics become even more tied to national politics because Student Centers are the main space through which students communicate and debate with the university’s upper management, politicians, and diverse social movements.

This link between university and national politics is critical for understanding the CECSo election outcomes. La 15 and La UES purport to have many political differences, but they both respond to many of the same representatives at the national level. For this reason, some students feel that the election outcome represents little more than a font change. It is especially concerning for leftist groups, since Peronist union leaders and national delegates have been complicit in many ways with Milei’s reforms. For instance, Peronist senators provided key votes to pass an investment regime that’s accelerating the decline of national industry. Furthermore, the Peronist leaders of the country’s largest unions have not come out against the security minister’s anti-picket protocol, which explicitly criminalizes peaceful protest. The founder of La 15’s national electoral coalition has even assented to classifying teachers as essential workers, a move proposed by Milei that would take away teachers’ right to strike. Peronist delegates’ serial compliance with Milei’s reforms invites doubt about the possibilities to recuperate university funding with La 15 at the wheel.

Despite Milei’s veto, the second Marcha Federal Educativa on Wednesday was in many ways still a win. In the college of social sciences, diverse student groups marched together behind the CECSo, demonstrating the potential for diverse currents to cohere when the moment calls for it. The march also showed the enormous level of support that Argentinians have for public university, and their willingness to unite in the streets to defend it. This is critical leverage against an extremist and openly anti-democratic government.

However, activating this leverage continues to depend on the initiation of union leaders to call a strike and mobilize workers. The leaders of Argentina’s largest unions have shown themselves to be timid in this respect, instead following a “wait and see” philosophy characteristic of Peronist verticalism. This approach will not cut it against an administration that can only be confronted with a radical and sustained plan of action.

Wednesday’s march was only one step in what will surely be a long haul. The success of this haul will depend in part on the ability of La 15, at the head of the CECSo, to construct students’ struggle within the fight for an economic and political structure with working-class Argentinians at the center. But it does not depend only on La 15: in order to achieve dignified working conditions and accessible education, the student body as a whole—not just a political fragment in charge of institutionally representing them—must articulate with diverse movements over the coming months, from retirees to public hospital workers; teachers and professors to small business-owners. The strength of these movements is not at the ballot box but in the streets, where, as Wednesday’s march showed, they can take back their rights, their labor, and their future.