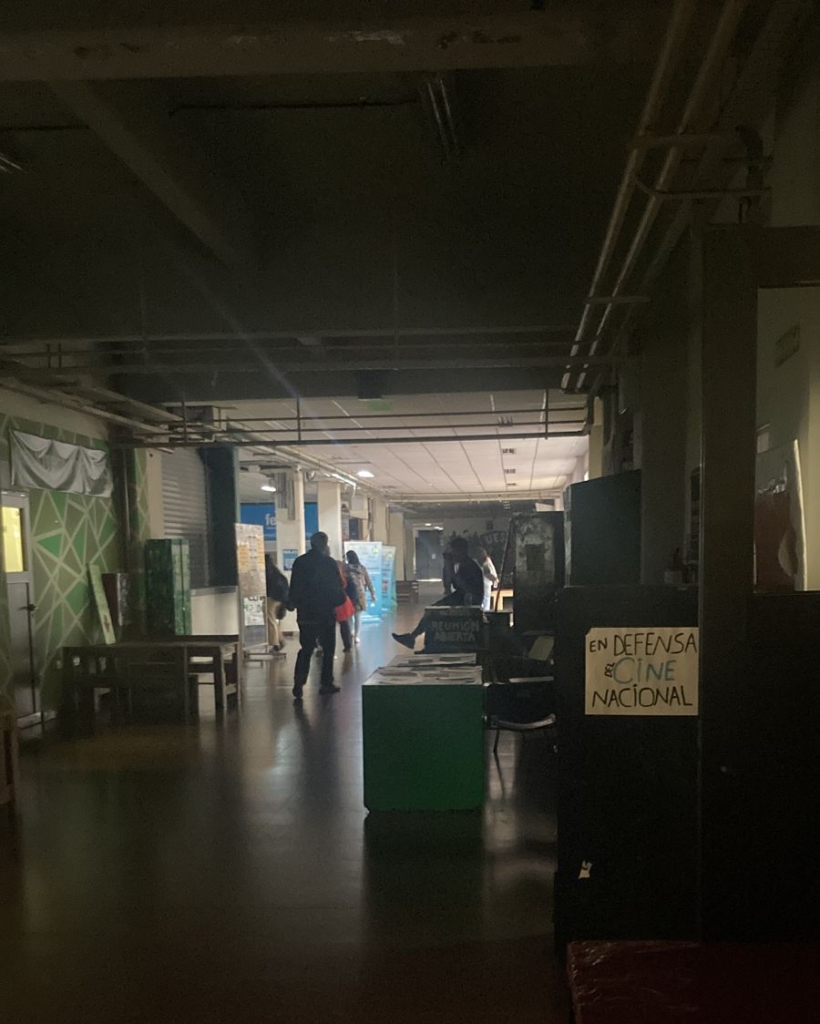

At 4am, after many hours of planning, painting, and milling around—ok, mostly milling around—I hit a wall. I abandoned the fluorescent lights and rock nacional spilling from SG100, wandered into a dark classroom, and rolled out my mat. Not all my compañeros were so fortunate; most had passed out right on the floor. But even they would be well-rested compared to the rest of the equipo, who were still in SG100 finishing banners and t-shirts for the day’s march. Though me and 100 other students were held together that night by the grace of Charly Garcia and yerba mate, we occupied the social sciences building in defense of something even more dear to Argentine identity: public education.

In February, Argentina’s interannual inflation reached 276% (% inflation since the previous February), which amounts to a massive cutback for any government institution that isn’t compensated accordingly. That has turned out to be a lot of sectors, since in October of 2023 Argentina voted right-wing anarchocapitalist Javier Milei into office. Over the past few weeks, public schools have become an epicenter of resistance to his austerity “chainsaw,” especially as they’ve come under fire: none of Argentina’s 66 public universities currently have enough money to finish the school year. Students have spearheaded the struggle against these cuts by blockading the street with professors to give classes, holding self-organized assemblies, pressuring the country’s enormous union sector for a general strike, setting up days-till-shutdown clocks, and, as I found myself doing on Monday, occupying the campus overnight.

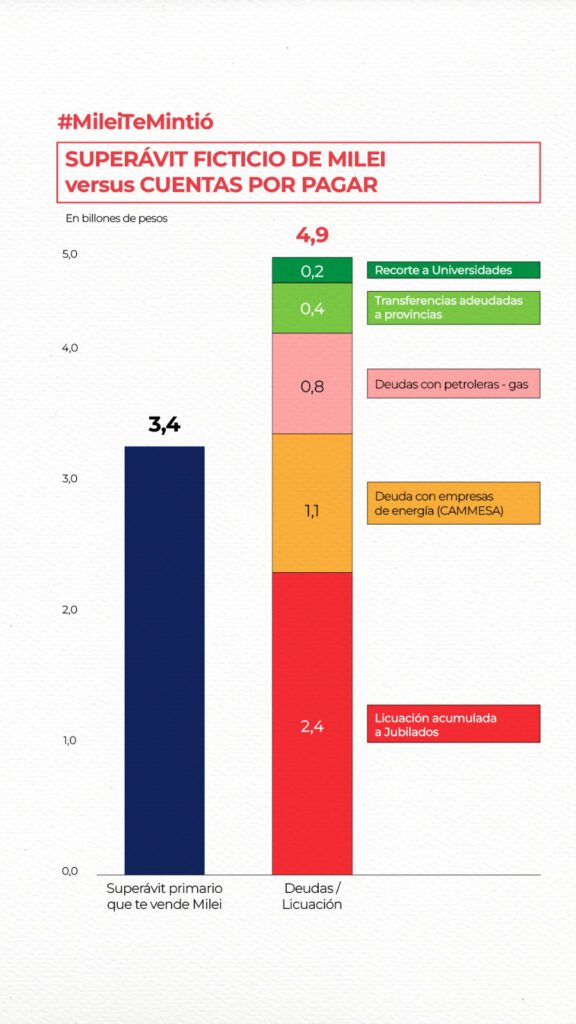

Milei ran on the platform of sacking Argentina’s casta, or political class, which he (not unfairly) blamed for 20 years of corruption and mismanagement since the country’s economic crisis in 2001. On Monday, April 22nd, he announced Argentina’s first fiscal surplus since 2008, and celebrated the success of his plan. How did he manage this miracle that no other president could?

The answer comes from two main moves: cutting pensions and postponing debt. While slashing social services is textbook for any neoliberal government, Milei’s main feat is maintaining an anti-casta narrative in which he achieved the surplus by toppling political elites and cracking down on corruption. The numbers show that Argentina’s most vulnerable sectors are actually footing the bill of his “economic miracle.”

Although university spending represents a relatively small slice compared to retirement and infrastructure, it’s also one of the most poorly funded institutions, given its quality of instruction and research outputs. For perspective, in 2023, the University of São Paulo (Brasil) spent roughly US$15,000 per student, and the National University of Mexico, US$7,968. UBA, meanwhile, invested just 1,123 dollars per student (despite the budget gap, QS ranked UBA at 67th worldwide; University of São Paulo and Mexico both fell just outside the top 100). In my 9 (!!) months here (admittedly, as a student at UBA), my sense has been that the university is a pillar of prestige for Argentinians; at the very least, it represents a site of equal opportunity and professional development in a context of increasing poverty and precarization of labor (60% of Argentinians live below the poverty line as of January 2024). Milei put his chainsaw to that pillar, reaching fiscal surplus by threatening to leave professors, TAs, and sanitary workers, many already living on poverty wages, with no job at all. He cut water and electricity to Argentina’s crown jewel institution and then patted himself on the back. Milei, in other words, poked a bear.

On Tuesday, the bear poked back. By 4pm, over half a million people filled the Congressional and Presidential plazas of Buenos Aires, spilling onto the avenues beyond any drone camera’s view. Drumbeats gave rhythm to banners’ advance as organizations of students, teachers, workers, alumni, and even musicians, all marched to defend public education. The mobilization was larger than the nationwide general strike on January 24th and the march on March 24th for Memory, Truth and Justice, a day which commemorates Argentina’s civic-military dictatorship. Tuesday’s numbers also broke records in other provinces, totalling another half-million protestors country-wide.

Although the protest’s scale and urgency were main talking points, a deep, radiant pride also shone through that afternoon. One first-year UBA student I interviewed said, “More than anything, for those of us just starting our majors, it’s like they want to take our dream away. We all want to study, too, because it’s what gives us a future… of all the shit in this country, public education is one of the best things we have, without a doubt.”

Milei backtracked after the march, tweeting that “We’re going to guarantee the funds for universities and audit how they use them.” But if he wanted an audit, he could have Googled it—public universities, being public, publish their expenses every year (here’s UBA’s full 2023 report). He also added that “the national government never insinuated the intention to close universities,” which may be confusing for students who spent the last week in dark hallways due to his cutbacks.

If not a shutdown, Milei certainly insinuated something when he wrote in February that “all careers that aren’t medicine or engineering are useless for society.” Now, even if your only measuring stick for social utility were profitability, this wouldn’t be true. But more importantly, I don’t think we should take Milei on his word here: it’s not that he wants to eradicate sociology and film and literature; rather, he only wants a certain strain of them: one that is useful for capital. His complete defunding of the National Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual Arts (INCAA), for instance, has dismantled Argentina’s national film industry, a vital way that the country constructs and celebrates its identity. The move, however, also opens the market for foreign cinema: more Hollywood, more subtitles, more imported culture. Milei doesn’t hate film, he just wants it in bed with global capital.

The same logic applies, I think, for academics. Last semester, I took a philosophy class at Argentina’s Catholic University (UCA) that overwhelmingly presented moral justifications for orthodox economics. During the course, I saw that even the “pure humanities” villanized by Milei can be turned into ethical supports for abject poverty in the free market. The private education model, rather than eliminating “non-productive” areas of study, actually develops them insofar as they justify the conditions for capitalist production.

This means that students and educators are not in a fight for sociology (or x “socially useless” field of study), but a certain interpretation of sociology. I think a struggle “for sociology” risks missing that sociology does exist in Milei’s freewheeling anarchocapitalism, even if it’s a husk of a discipline. Instead, we should call attention to diverse disciplines as instruments of power—both to liberate and oppress—as part of defending their gratuity and accessibility. This articulation is also stronger because it conveys an underlying claim that the first one doesn’t: there are certain areas of life which we should not leave to the market.

The idea that certain things like education shouldn’t be capitalized is the whole point of talking about them as a right. Since power in this case is expressed as a redefinition (not prohibition) of humanities and social sciences, fighting for an alternative means moving towards specific conceptions of those disciplines, beyond just their existence. For example, two aspects of sociology that are important to me are its de-naturalization of existing social relations (as in, it doesn’t set out to explain why our system is the most natural way for humans to live) and its accessibility to anyone, which I think is the state’s responsibility to ensure. From this point, we can debate and disagree and fine tune, but I reflected after the march that, especially with education, we should never lose an opportunity to critique the social formations that produce the disciplines being contested, taking those structures as a point of departure rather than the fields’ mere existence.

In the past few months, I think this kind of discourse has been highlighted in the case of INCAA/Argentinian national cinema. When people occupied the street outside a historic cinema, for instance, it was not a protest against the “death” of cinema, but national cinema as culturally valuable and historically unique. That specific theater was a rallying point for social movements because it represented filmmaking as a practice which incorporates and critiques the conditions of its production. The specificity of protestors’ claims and they way they disrupted space turned out to be crucial because when the police confronted and tear gassed them, the scene demonstrated, without words, how the reproduction of capital undermines cultural autonomy and critical art forms.

And so it comes to this: the way you position yourself and a claim, both in conversation and in space, affects how conflict happens. This was the success of the Madres de la Plaza de Mayo, who did not come to the plaza merely to protest the dictatorship, but as mothers demanding the return of their disappeared sons and daughters. The Madres’ legacy in social movements is so powerful because they articulated their denunciation of the dictatorship through the notion of a mother as caretaker; by making the violence of rupturing that relationship impossible to ignore; by challenging the government to negate their grief. Through this, the movement laid out a new interpretation of the disappearances; a new social and emotional terrain in which the dictatorship itself was understood. As my favorite sign at the march asked: “Milei: why so scared to educate the people?” The rhetoric of the question encapsulates the contradictions of the president’s politics; that is, the incompatibility of his economic program with citizens’ social rights. From the recognition that politics is a struggle for interpretation, social movements should continue to foreground the everyday victims of Milei’s government, using the disaffection of popular sectors to construct solutions to the conditions and failures that made his rise possible.

I’ll conclude with a question I’ve asked myself many times: by what divine illumination does a yanqui march into a cause so close to the white-and-turquoise heart of Argentinians? I have come to justify my involvement by the simple recognition that, despite its particularities, Milei’s ability to capture and channel a nation’s frustration is global. He’s not a “global phenomenon” because his demeanor has a prototype—forget Trump, Bolsonaro, and Johnson—but because the multiplicity of lefts, on a global scale, have been unable to turn masses’ sheer anger at the system into a scalable alternative. And if saying that was a tired slogan for the students of May ‘68, what does that say about the left’s gains since then? I march for public university in Argentina because I’ve seen what increasing privatization of a public university does to the living standards, mental health, and educational outcomes of its students. I know, too, that some students at public university in the richest state in the world’s largest economy go into debt for something we recognize as a basic milestone and human right in the poorest countries in the world. I march because the burden of decreasing state funds in Argentina will be passed on to students, as it has at UCSB, where undergraduates, despite paying 50% of the university’s revenue, are squeezed each year into fewer houses and weedier weeder classes. I mobilize for that same cause 6,000 miles away on the reflection that I have an obligation to learn from a student body that’s not afraid to organize (my second-favorite sign from the march: “Voldemort was defeated by organized students”). And if I’m honest, I protest because it makes me feel OK in the world to know I’m not the only one with a bit of boiling rage that I’d love to turn into Something Beautiful. On Tuesday, I marched for a cause so close to the white-and-turquoise heart of Argentina because working across borders to debate, brainstorm, and build that Something is the best way forward I know.

This blog was originally mailed on April 26, 2024