When you lose a mundane thing (let’s say a pair of earbuds your really like), there’s often a window between when you lose the item and when you realized you’ve lost it. In this “overlap period,” two realities coexist: one in which the earbuds have been lost, and another, your reality, which is completely undisturbed by this fact. At a certain point, these realities realign. Your perception of a nice world where you have your earbuds in your back pocket is fractured and you are taken by worry, anxiety, and grief.

Anthony De Mello would say these emotions are the effects of Attachments. An attachment is a thing that we believe our happiness depends on. Being an attachment is not an intrinsic property of a thing, but becomes an attachment in relation to a person. Specifically, attachments fill a lack that we perceive in ourselves, and make us feel whole. The object takes on a position relative to our desire and we give it a special importance.

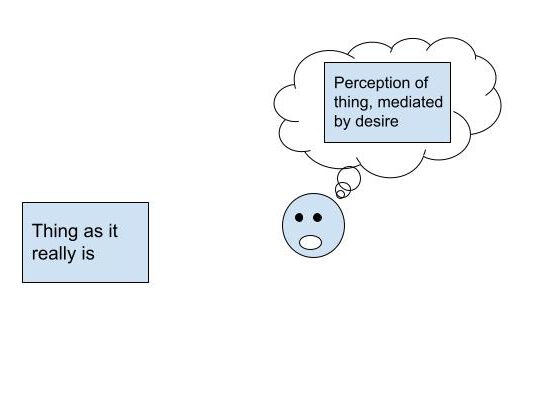

In general, attachment seems to imply two distinct realities. First, there is the object as it really is: a thing, out there in space, with no essential importance. Then, there is our perception of that thing, in which it becomes nice or beautiful or ugly.

Usually, we think of reality as the collection of “Things as they really are.” For instance, a Nike shoe is “just a shoe,” but our attachment to the brand blinds us and causes us to overvalue it. When we lose the earbuds, we might say, “Oh well, things are just things!” This statement is a recognition that our grief for the earbuds is a function of our frustrated desire. It implies the existence of an unmediated reality that is more fundamental than our tainted, attached perception of it.

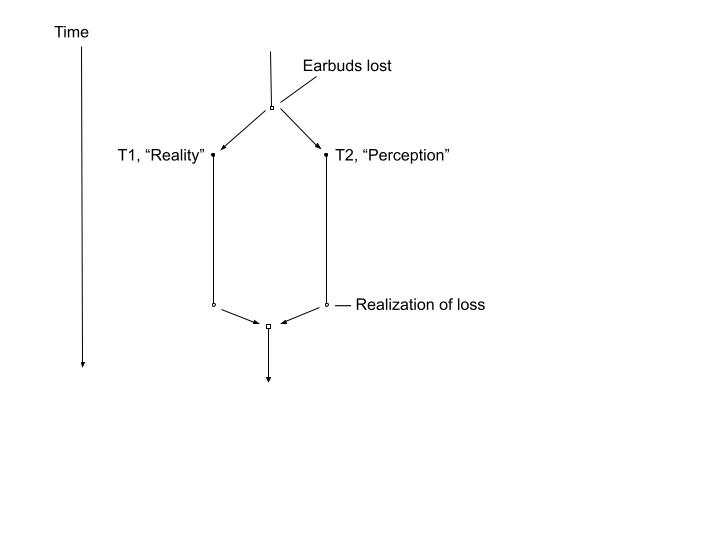

Let’s draw a timeline of losing our earbuds:

We are inclined to call T1 “reality” because, after the fact, we know the earbuds were lost before we realized it. If you left them at a coffee shop, there’s no question that the whole time on the bus home and cooking dinner and doing all these other activities, your earbuds were already gone.

But your experience of the afternoon was completely undisturbed by the object’s absence. T2—your blissful, undisturbed, perception—was the realest, and indeed the only, thing there was. T1, the timeline we are inclined to call reality, was only “realized,” or made real, after the fact.

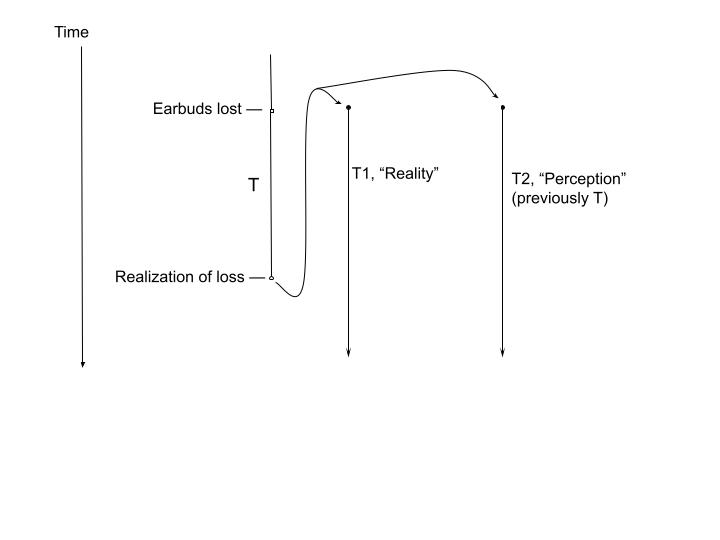

When we acknowledge that T1 is brought into existence retroactively, we also recognize that the individual—along with all their desire and other distorting baggage—causes it to become real. Your realization of loss not only produced the emotional effects of your attachment, but literally brought T1 into existence. This maps onto the origins of the word “realization,” which comes from the French réaliser, meaning literally “bring into existence” or “cause to become real.” Our mediated reality is the very thing that allows us to retroactively posit an unmediated, presubjective, or underlying substrait of reality. But T1 is none of these things: indeed, what we call the “truth” of the matter is a retroactively constructed reality which the individual’s “distorted” experience causes to exist.

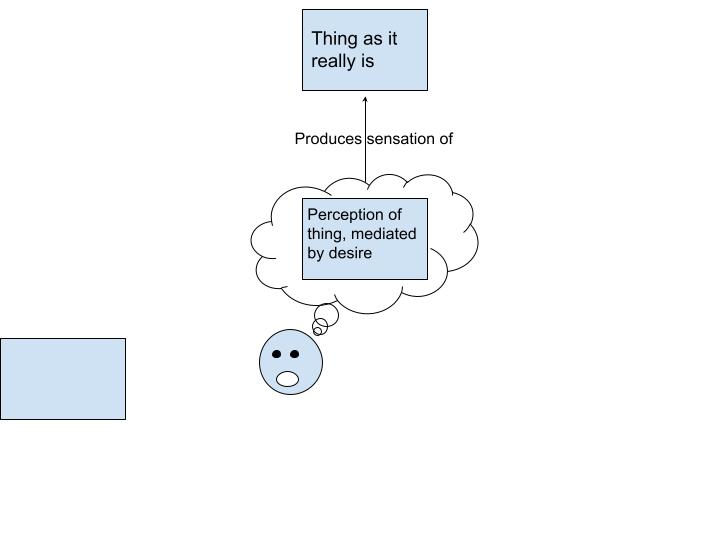

Furthermore, T1 is only brought into existence because of your attachment in the first place. If your relation to the object was not mediated by your desire, its loss wouldn’t even register as a significant event. There would be no retroactive split between T1 and T2, since they are only differentiated by the incongruence between your emotional state and the status of your earbuds. De Mello is right in pointing out that if you detach your happiness from the laborious and neurotic arrangement of things in the world whose nature is to change, disappear, and disappoint, you can avoid the suffering of loss entirely. But I don’t think we should read his account of attachment as a return to a “more fundamental” reality. Rather, since objectivity can only be posited from the position of a desiring individual, we should read De Mello as a recognition that lack structures reality itself. Indeed, the very thing he explores is the suffering caused by a refusal to see that our relationship to lack is structural, and only filled by contingent, constantly changing objects.

What De Mello hits on with his account of the thrill-disappointment-boredom cycle of attachments is that the hole that attachments fill isn’t going anywhere. We can either go from thing to thing, chasing excitement which we mistake for happiness, or we can accept lack and the desire to fill it as a structural condition of our existence. Either way, though, our perceptions of the world are always embodied as lacking individuals. There’s no way to get a perfectly linear relation between the world and our experience of it, an “absolute” reality unmediated by desire.

I’m going to leave it at that for now. The main thing I wanted to explore is how the gap between losing a mundane object and realizing you lost it demonstrates how the idea of a reality “underlying” or previous to our perception of it is always retroactively reconstructed from the position of a desiring subject.

Lastly, I’ll just say that everything I just argued, you can experience for yourself! If you ever think you lost something but aren’t sure, don’t immediately go look for it. Experiment with the feeling of not knowing. Notice that there is an “absolute” truth about whether the thing is lost or not, but that your experience of the world—and especially your reaction to the situation—is completely structured by your attachment to the object. And notice that your experience—not the actual, ontological lost/not lost status of the thing—is reality! See that truth, which at the moment is inaccessible to you, can only be established in hindsight, after you definitively do or don’t find the object. That truth, which you are yet to discover, will only come about because your lack, desire, and attachment impulses you to go looking for it.

Until next time,

Lucas